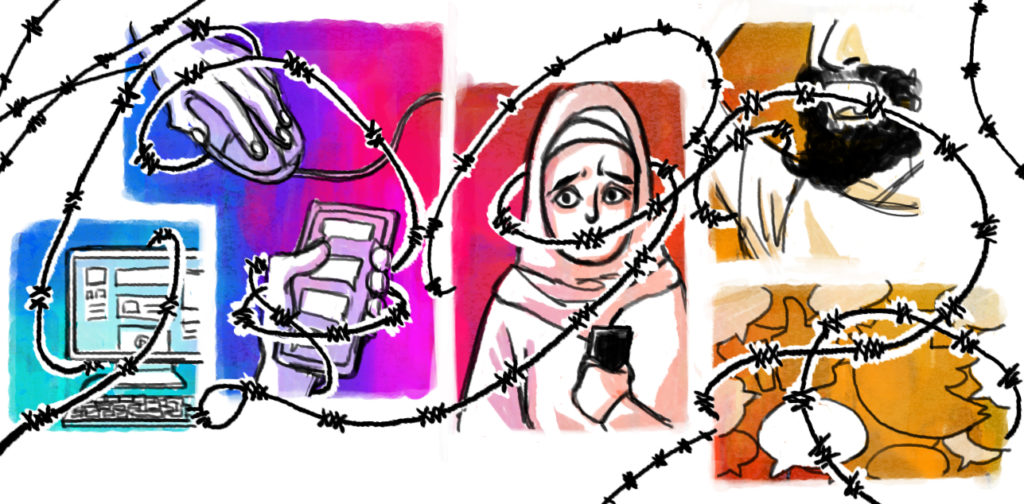

Over the past few years, many countries have either enacted or updated current “cybercrime” laws, including in the Middle East and North Africa (MENA) region. These efforts, while purportedly aimed at addressing increased threats to national security, in many cases have produced deeply flawed legislation that puts human rights at risk.

Access Now, the Association for Freedom of Thought and Expression (AFTE), and more than 40 other leading human rights NGOs have published a statement calling for the full repeal of Egypt’s Anti-Cyber and Information Technology Crimes Law (the “Cybercrime Law”) and the reform of dangerous media regulations that will further close the space for public debate and prevent the exercise of the fundamental right to freedom of expression. As the coalition writes, “[t]hese actions must be opposed in order to defend Egyptians’ human rights.”

But as this important piece by Global Voices points out, this issue is not confined to Egypt, and the context for these laws often make them even more dangerous. All across the MENA region, human rights defenders have been subjected to a wave of arrests and convictions in an escalating assault on the right to freedom of expression. These defenders are at risk in part because the laws they are prosecuted under are at once too broad and too vague, granting government authorities enormous power to control the flow of information and silence dissent. Accused of publishing misleading information (“fake news”), bloggers and journalists are arrested, charged, and in some cases, dealt harsh penalties — such as a 10 year-prison sentence — based on what they say or do online.

Below, we take a closer look at how regulations for cybercrime are harming at-risk people and communities, including journalists and human rights advocates.

Cybercrime laws raise the stakes for everyone, but especially journalists and HRDs

Cybercrime laws are slowly becoming a primary enemy to the free press. These laws can relegate to state security apparatuses full and comprehensive control of the media. They are similar to the government “state of emergency” declarations that a number of countries have put in place, and can serve to increase the number of people who become suspects of crimes like violating national security, or spreading confusion and incitement. Here we look at the extent to which cybercrime laws have been implemented in a number of Arab countries, and the impact on average social media users as well as human rights defenders, who are often put at greater risk.

Egypt

The Cybercrime Law permits the conviction of anyone under the pretext of “threatening national security,” “harming family values,” or “influencing public morals” without providing a clear definition of these crimes. This law has led to restrictions of the freedom of expression, whether through repressing critical speech, as in the case of journalist and blogger Wael Abbas, or through legislating the blocking of websites, as provided under Article 7. This contravenes Article 19 of the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR), which states:

“1. Everyone shall have the right to hold opinions without interference. 2. Everyone shall have the right to freedom of expression; this right shall include freedom to seek, receive and impart information and ideas of all kinds, regardless of frontiers, either orally, in writing or in print, in the form of art, or through any other media of his choice….”

Besides that, it does not comply with Article 56 of the Egyptian constitution, which states:

“freedom of thought and opinion is guaranteed, and all individuals have the right to express their opinion through speech, writing, pictures or any other means for expression and publication.”

Read the global coalition statement for additional details showing why this law must be repealed in full.

Lebanon

Lebanon does not yet have a law regulating cybercrimes. However, domestic security established a cybercrime office in 2006, known as the Cybercrime and Intellectual Property Rights Bureau, which is under the jurisdiction of the judicial police. In the absence of a law regulating internet activity, the bureau relies on the Audio-Visual Media Law of 1994 (the law regulating television, radio, and newspapers) and the Lebanese Penal Code of 1943 for issues in the online space. Establishing the bureau has increased the threats to freedom of expression, since it responds to malicious complaints, such as those against activists including Ahmed Shoman, and can force activists into silence by requiring them to sign pledges promising to cease their activities, as it did activists Mohamed Awad and Elie Khoury.

Furthermore, as documented by our partner Social Media Exchange (SMEX) in Lebanon, the number of activists called up for investigation due to posts on social media platforms that criticize politicians and religious leaders increased from three activists in 2016, to nine in 2017, and now 16 activists in 2018. Additionally, it should be noted that there are numerous of laws that regulate cybercrime in Lebanon such as Law (No. 140/1999) on wiretapping; Law (No. 75/1999) related to the Protection of intellectual property – addresses part of the issue of computer security and especially piracy programs (Articles 83 to 89); Law (No. 431/2002) related to communication; Law related to patents (Article 240 August 7th, 2000); and Draft law related to the electronic transactions (amended in T. 22 008) At the stage of final approval. Although freedom of expression is guaranteed under the Lebanese Constitution, the ongoing arbitrary actions taken against journalists and activists have weakened the rule of law and trust among Lebanese citizens in the capacity and truthfulness of the Lebanese state.

Palestine

In June of 2017, President Mahmoud Abbas approved a cybercrime law in Palestine. Local civil society organizations opposed the law and raised serious concerns about it, as it directly authorized violations of the right to freedom of expression online. As a result of civil society efforts and advocacy campaigns, the cybercrime law was modified and approved in April 2018, but it remains dangerous. Contrary to what the government claims, the effect of the law is not to safeguard and protect public freedoms, such as public safety and security. Instead, it restricts and suppresses these freedoms. The law contains vague terms and concepts that Palestinian authorities can easily manipulate. The most prominent examples are Articles 16, 20, and 51, which put users at risk of punishment with a fine or a prison sentence under vague charges such as “threatening the security and integrity of the State,” and “inciting racial strife and harming national unity.” The arrest of dozens of journalists and activists, including Ahmed Awartani and Ibrahim al-Masri, took place after the law came into force in 2017, before it was modified. The provisions contravene the human rights commitments that Palestine has made as a party to the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR), as well as Palestinian Basic Law, in particular Article 19, which affirms:

“Freedom of opinion shall not be prejudiced, and all individuals has the right to express their opinion and to publish it, either orally, in writing or in other means of expression or art, subject to the provisions of the law.”

Bahrain

In September 2014, the Cybercrime Law in Bahrain came into force, regulating “information technology” crimes. The law is complemented by other pieces of legislation including media and telecommunication regulations and counter-terrorism laws. Restriction of freedom of expression in Bahrain is based primarily on the Media Regulation Law of 2005, in particular Article 70 of the text. The regulation gives authorities significant discretion when implementing its provisions, as was the case with the prosecution of human rights activists Nabeel Rajab and Abdullah Al-Sinjasi. The Cybercrime law, meanwhile, gives various government organizations, including the Ministry of Interior and the Ministry of Public Information, the capacity to block and censor a wide range of websites. No court order is needed to censor websites that host content deemed a “challenge” to the government, such as, for instance, any published content that is critical of the Bahraini government, the royal family, or the status quo, as we saw in the case involving the Al-Wasat newspaper.

Next steps? Reform laws that undermine human rights and support use of the internet for free expression

Following the wave of uprisings that took place in 2010-11, Arab governments have turned to suppressing online speech to protect their interests. Initiating “cybercrime” laws has since become a pathway for stopping protests or fighting opposition.

Cybercrime laws have also been expanded to grant authorities the right to confiscate electronic devices, block websites, and punish and hold service providers accountable for the content published via their services. This opens the door to service providers spying on users en masse in an effort to escape liability.

This trend must be stopped. Before they move forward with additional legislation, we urge governments to review the strategy behind these laws and assess the negative impact they have, not only on journalists but on all internet users. Simply for exercising their fundamental right to free expression — protected under international human rights laws — people are being prosecuted, deported, or jailed for what they say when they comment on posts, for blogging, or for sharing images that have social, religious, or political content that may challenge those in power. The laws are so broad, it is easy for people to misstep. Only with clear and unambiguous standards and concepts in the law can we protect people’s fundamental right to speak out. As it stands, this right is in jeopardy, while laws that are supposed to address the real crimes committed in the online space, such as fraud or identity theft, are failing.

A positive agenda for MENA governments would be to increase the use of the Internet as a platform of communication. The internet can be an effective tool for education, health, trade and economic and social development. Improving digital security is an integral part of this effort, as is expanding universal access to information communication technologies (ICTs). Protecting human rights online is a core part of online security.

Cybercrime laws should not conflict with the fundamental rights and freedoms guaranteed by international law and human rights. Access Now will continue working with stakeholders across the region, including at RightsCon 2019 in Tunis, Tunisia, and at the international level at the United Nations Human Rights Council, to ensure these and other laws do not undermine these rights.