Social media is increasingly becoming the dominant means of communication for this generation. Both the revenues of social media platforms and the number of people using them are rising across the globe. This is a largely positive process; the open and free internet empowers and enables the exchange of ideas and allows the global community to thrive.

However, that which can be used for good, can also be used for bad.

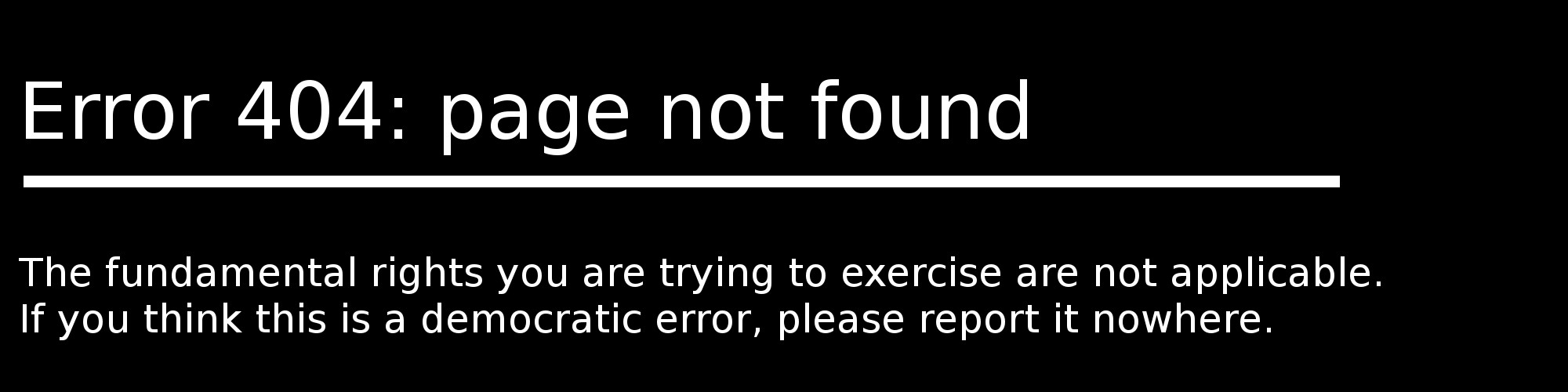

The emergence and spread of terrorist and violent extremist online content seems to baffle governments. In a haphazard effort to combat this, legislation across the EU is being tabled with inadequate definitions, little to no oversight or redress, no explicit accountability, and no transparency reporting. This is alarming, tone-deaf, and entirely counter-productive.

The Internet Referral Unit

Europol established its Internet Referral Unit (IRU) in the spring of 2015, though it only became legally anchored through the Europol Regulation passed in May 2016. The term “anchored” is used very deliberately here; the Regulation did little else in setting the terms for the IRU, and did not establish transparency or accountability.

The IRU is meant to support EU states in preventing and combating serious forms of crime (read: violent extremism, human trafficking, child exploitation, etc.) which are committed through the internet. The unit is meant to do this by referring illegal internet content to online service providers for their voluntary consideration. The providers are then free to evaluate the illegal content against their own terms and conditions, and subsequently remove it if they see fit.

This is outside the rule of law on several grounds. First, illegal content is just that — illegal. If law enforcement encounters illegal activity, be it online or off, it is expected to proceed in dealing with that in a legal, rights-respecting manner. Second, relegating dealing with this illegal content to a third private party, and leaving analysis and prosecution to their discretion, is not just lazy, but extremely dangerous. Third, illegal content, if truly illegal, needs to be dealt with that way: with a court order and subsequent removal. The IRU’s blatant circumvention of the rule of law is in direct violation of international human rights standards.

Commissioner Dimitris Avramopoulos said that “the IRU will provide operational support to member states on how to tackle more effectively the challenges of detecting and removing the increasing volume of terrorist material on the internet and in social media.” To give credit where credit is due, it has succeeded in reducing the volume of such material. But whether that is even correlated to ending the spread of these ideas is doubtful. To date, the unit has established 25 individual IRU national contact points and assessed 7.364 pieces of online content, which triggered 6.399 referral requests with a success rate of 95% for subsequent removal. That is a lot of take-downs.

While illegal content online is a pressing issue, it needs to be dealt with in an appropriate, rights-respecting, and democratically sound manner. Simply, certain rights are non-derogable.

Removal or retention?

The EU’s Check the Web project has been running most of the intelligence gathering activities proposed for the IRU since 2007. This project has been working across EU institutions and member states in order to assemble online intelligence from as many resources, in as many languages, as they can. In 2016 alone, 629 new terrorist media files were uploaded to the Check the Web portal. This information (contact persons, link lists, statements by terrorist organisations) is used across the EU to build a comprehensive database and map of extremist online activity. It seems counter-intuitive to follow this data accumulation with the establishment of the referral unit, which will be tasked with removing exactly that content.

UN and human rights groups rebuke the common approach

The issue has not gone unnoticed by those working to protect human rights. They are challenging the rights-oppressive model that is now being imposed on most of our societies. They point out that the approach of referring and removing content via third parties — trumpeted by EU’s Internet Referral Unit — risks further alienating targeted individuals. As noted by the United Nations General Assembly in its Plan of Action to Prevent Violent Extremism, state-run removal of online activity, subjugation, or foreign intervention can actually feed into narratives of victimization.

The failure to adequately — and accountably — investigate and deal with violent extremist content could serve to alienate and isolate individuals and online communities. In the end, we may see them finding alternative ways to communicate their messages, and having law enforcement and government agencies suppress their speech may only increase their recruitment capabilities.

Banning words does not lead to social harmony. That is a strategy of oppressors. That’s something we need to remember, even as we battle to counter the narratives of terrorists and criminals online.