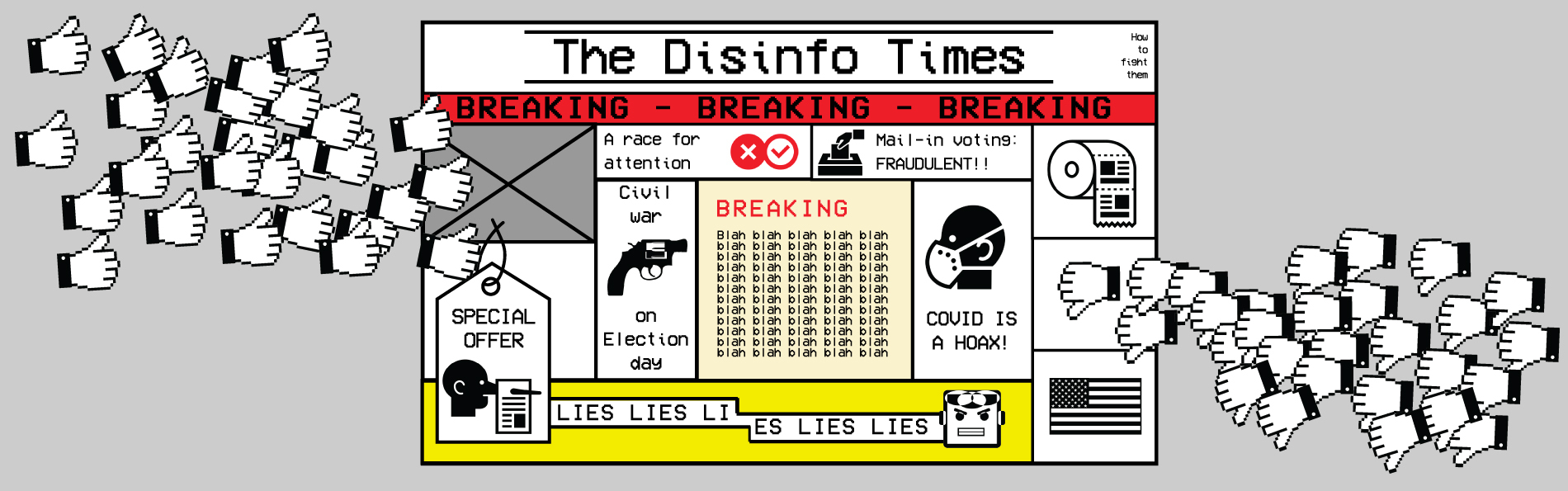

Political advertisement can be a powerful driver for dangerous disinformation and propaganda online. It is often linked to platforms’ data-harvesting and exploitative business models.

The EU has proposed a timely Regulation to increase transparency for political ads. The proposal however may not go far enough to protect people from covert manipulation.

But what are political ads, exactly? What does the EU proposal say? What is its potential impact on Europeans’ rights and personal agency in the online environment? This FAQ has the answers for you.

Q: What are political ads?

A: Under the draft EU Regulation, political ads are defined as political messages that are directly or indirectly paid “For or on behalf of political actors”. They do not include statements of support for political candidates expressed in a purely private capacity.

More specifically, the Regulation defines political ads as: “the preparation, placement, promotion, publication, or dissemination, by any means, of a message, which is liable to influence the outcome of an election or referendum, a legislative or regulatory process, or voting behaviour”.

Political ads are not only ads placed during electoral periods, but any time, in contrast to many national laws in this area. In France, the EU country with the most developed legislation governing political advertisement, regulations forbid online political advertising during the six months preceding the first day of the month of the elections. Hence, the EU’s proposed approach is more ambitious.

While this kind of novelty can be a strength, it also opens a space for potential abuse. In fact, some EU countries, like Hungary or Poland, have used the need to comply with new EU laws on transparency as a justification to crack down on civil society organisations and activists. Since the Regulation offers a broad definition for political ads, it could easily include the political campaigns of civil society organisations on a number of societal issues, such as adequate access to information, or anti-corruption. EU legislators must address this problem in the coming months to ensure that established non-governmental organisations are able to campaign and raise public awareness on matters that are relevant, including when an issue is related to elections and government activities.

Q: What is the goal of the proposed EU Regulation?

A: The purpose of the Regulation is to protect electoral integrity, the plurality of opinions, and democratic principles at the core of the EU. EU policymakers want to mitigate the effects of online disinformation and prevent foreign interference in EU elections.

The proposed Regulation is centred around harmonised rules for a “high level transparency” for political ads and related content for political campaigns. It contains new obligations for “political advertising publishers”, a term that includes individuals, broadcasters, platforms, or anyone else who brings political ads into the public sphere.

Q: Who will have to follow these rules?

A: The scope of draft Regulation includes a wide array of political actors, from political parties to political campaign organisations. It uses the whole-of-value-chain approach, establishing a specific set of obligations not only for online platforms but also other players that regulators often overlook at the national level.

To understand the real scope of the proposed Regulation, we need to go back to its foundation. One of the key functions of the EU is to harmonise the European internal market by creating unified legal standards that will apply equally across its Member States. However, the EU is only allowed to issue harmonised legislation in those areas that Member States entrusted to its competence. And that’s where the problem arises — regulation of national electoral systems is the exclusive business of Member States. However, considering that some EU governments blatantly abuse their powers to disrupt the fairness of elections, we welcome EU action in this area. The EU will have to carefully act within its powers to implement measures in the context of elections that help safeguard agreed EU values and freedom, including the rule of law.

Q: So will the proposed Regulation regulate national elections?

A: In principle, it cannot. However, there might be a good reason why it is proceeding with a proposal that raises this question. The proposed Regulation creates a new set of obligations for a wide range of actors and types of communication. These obligations, such as the transparency rules, should apply to all media, including newspapers, television, radio, and social media operating across the EU. While the EU has no direct competence to regulate national elections, the European Commission justifies this provision by pointing to the cross-border nature of the online environment.

It is important for the EU to step up its role as a watchdog over independence and legitimacy of national electoral systems. We are finalising this FAQ in the wake of the Hungarian national election. When Victor Orban commented on the sweeping victory for Fidesz, he proclaimed it a day when Christian conservative “democracy” won out over Western liberals. We are seeing a rhetoric of us versus them, a profound lack of media independence, state interference with independent elections, and the rise of state-sponsored propaganda, such as Russian pro-war propaganda, taking hold. This is in direct violation with the core values of the EU. Four years ago already, the OSCE deemed the Hungarian election “free but not fair”, due to the Fidesz government’s power and control over the media and its propaganda. In times like this, it is an absolute necessity to ensure a strong union that can call for meaningful accountability of its members, if we hope to see democracy prevail.

Q: Will the Regulation truly increase transparency for political ads?

A: The short answer is yes — it might. The draft Regulation champions a new set of criteria for increased transparency in political advertisement, including:

- the obligation to keep a permanent record of political ads, campaigns, and all related data;

- the requirement for user-centric, real-time transparency that demands, among other things, proper disclosure and labelling that specific content constitutes political advertisement;

- provisions to ensure clear, plain-language explanation of targeting and amplification techniques; and

- access to data that is granted not only to public authorities but also to vetted researchers and importantly, civil rights organisations defending the public interest.

The list of transparency criteria is exhaustive, but as always, the devil is in the details. Whether the increased transparency in political ads will be truly meaningful will depend on implementation of its big parent, the Digital Services Act. The draft Regulation directly refers to advertisement repositories to be constituted by the DSA, which will probably make them mandatory. In an ideal world, individuals should be able to go to depositories and find all required information in one place. However, neither the DSA nor the draft Regulation calls for the creation of “mandatory, cross-platform, real-time ad archives for political ads”, which would allow individuals to get comprehensive information without falling prey to misleading interface designs. To quote Dr. Julian Jaursch, this is a missed opportunity to create “a joint industry standard for political advertising transparency”.

Q: Will the Regulation prevent the use and abuse of personal data for the purpose of targeting and amplification?

A: Unfortunately, not really — unless some amendments are made to the text.

The most celebrated provision of the proposed Regulation is its ban on targeting and amplification techniques that involve using and processing special categories of personal data (i.e. sensitive data), as defined by the General Data Protection Regulation. It is certainly positive that lawmakers and the public increasingly see how some forms of targeted content, such as advertising based on online tracking, harms human rights. The data harvesting business models of large online platforms enable the advertising industry to develop data-driven targeting strategies. Through this approach, companies identify and exploit our behavioural patterns and characteristics.

It is therefore disappointing to see that the aforementioned ban may just be an empty shell that only holds symbolic value. This is so for two reasons.

First, the ban applies only to the use of sensitive data that is already prohibited by the GDPR framework and thus, only clarifies what is already established in an existing legislation. It is a missed opportunity that the Regulation does not further clarify that the ban applies to the use of inferred data for the purpose of targeting, optimisation of content, and amplification of dissemination of political ads. Data inferred from and combined with other information, online and off, can reveal very personal information and insights.

Second, the draft Regulation provides two exceptions from the ban: 1) individuals’ explicit consent and 2) legitimate activities by organisations defending the public interest.

To be frank, by including the explicit consent exception, the Commission shot itself to the foot. Targeting and amplification techniques are driven by opaque algorithms that can influence individuals’ freedom of thought and opinion. They are designed to manipulate individuals for profit. The deployment of these techniques often relies on people being coerced into saying “yes” thanks to deceptive design. In most online interactions today, individuals are not able to provide explicit, valid consent with a full understanding of what they agree to. Until we address this forced-consent situation, allowing political ads to be placed on the basis of consent is essentially an endorsement of the status quo.

Conclusion

The EU is facing unprecedented challenges in history when its own founding principles of democracy and the rule of law are shaking — both internally and externally. The democratic backsliding by some Member States is reaching unprecedented scale, fueled by the spread of targeted disinformation and state-sponsored propaganda. Therefore, the EU’s urgency in crafting a response is understandable and justified. As it develops new regulatory tools, we must ensure that laws motivated by good intentions meet their aim, and do not cause unintended harm. Access Now will continue to closely work with the European Commission to support this process.