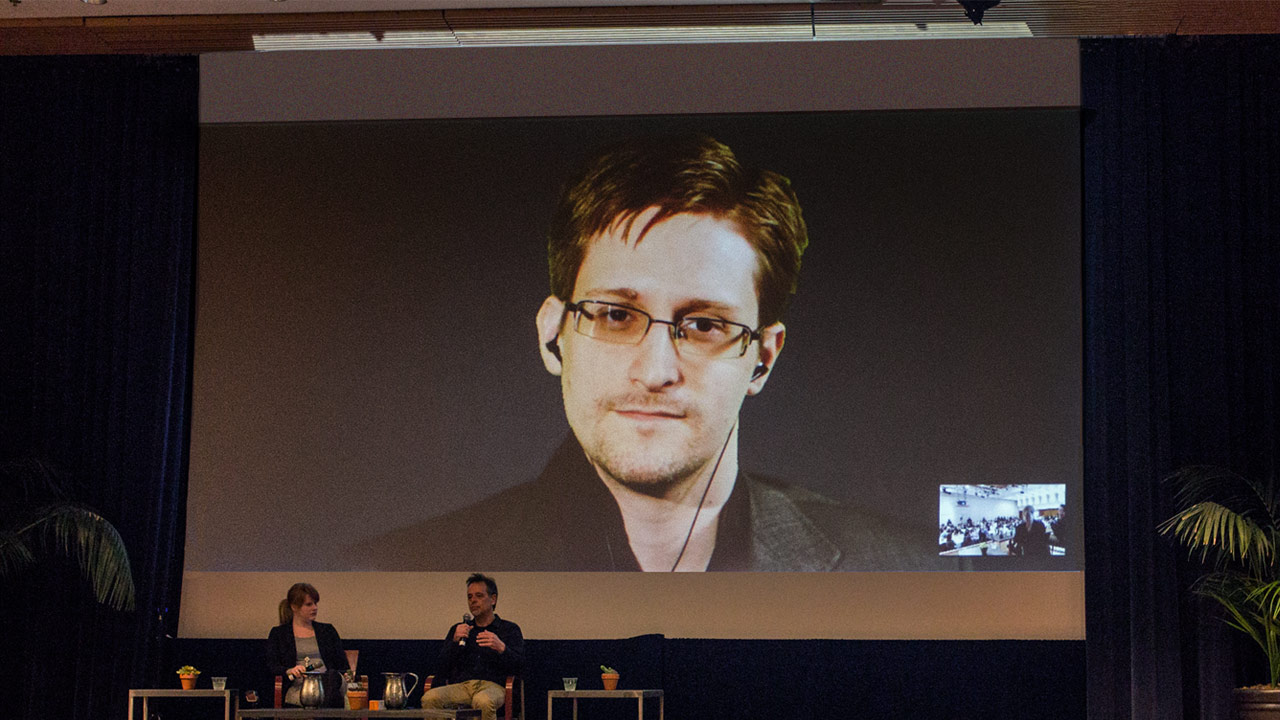

On January 17, 2014 — more than seven months after the first document was published in what we now refer to as the “Snowden revelations” — U.S. President Obama gave a speech at the Department of Justice that became known as the “NSA speech.” In it he discussed the scope of post-9/11 surveillance. He explained the significant steps that the administration had taken, and would continue to take, to review foreign intelligence surveillance, including creating an independent review group. He also acknowledged a man by the name of Edward Snowden.

On that day, President Obama did not credit Mr. Snowden for having instigated these reviews — the most comprehensive of national security surveillance since the 1970s. Instead, he cautioned that the disclosures were sensationalist, saying that they “spread more heat than light.”

We disagree. The past three years have made it abundantly clear that the light that Snowden shed on surveillance practices is vital to defending human rights worldwide. Access Now is proud to support the Pardon Snowden campaign asking President Obama to pardon Edward Snowden and allow him to return to the United States, and we hope you do the same.

President Obama had been in the White House for more than four years before the first Snowden document was published in The Guardian. At the time it was published, substantive reforms of the intelligence community were not even a twinkle in the eyes of members of Congress, regulators, or other oversight bodies. David Medine had only just been sworn in as chairman to the Privacy and Civil Liberties Oversight Board, a position that had been sitting vacant for the entirety of President Obama’s first term. Surveillance programs that would very soon be determined to be unlawful and unconstitutional by U.S. federal courts — and totally halted under the USA FREEDOM Act of 2015 — were in full swing, as they had been since the George W. Bush presidency. Surveillance authorities in the USA PATRIOT Act and the FISA Amendment Act had been renewed several times, including under President Obama, without adding any new protections. Civil liberties organizations in the U.S. spoke up against these authorities, but they may as well have been shouting into the wind.

Looking back, we can see that the debates over surveillance that President Obama was either unwilling or unable to initiate during those early years were only made possible because of Edward Snowden.

The “Snowden effect” is evident globally. For the first time in 33 years the United Nations has appointed a special rapporteur on the right to privacy, charged with safeguarding that right globally. In the private sector, Vodafone and more than 60 other companies responded to the information Snowden helped expose by adopting the practice of regularly publishing transparency reports on government requests for user data. This gives the public information necessary to participate meaningfully in the conversation on limits to government surveillance. Lawmakers in countries and regions globally have also responded. In Ecuador, legislators rejected a sure-to-pass data retention law, and the government reversed its position on it. In the European Union, government institutions rely on information from the Snowden revelations to argue repeatedly in court for stronger privacy protections when U.S. surveillance activities implicate the rights of Europeans.

The technology we use every day has changed. More of our data traffic is encrypted. Companies have made products like messaging apps more secure. People are adopting better basic security practices online.

We are often asked if Edward Snowden is a hero or a traitor. But that question distracts from the important issues that Snowden made it possible for us to understand and act upon. It ignores the fact that the exposure of these issues has led to debate, official reviews, and other public discussions — in Washington, D.C., Brussels, Brasília, and elsewhere around the world — leading to significant reforms. It ignores how much more we know about government intelligence gathering, and about companies’ collection and use of our personal data, than we did before Snowden took action. It ignores the value of this information to defending our human rights and the rule of law, all around the world.

We agree with President Obama and with Edward Snowden himself that the important story of the revelations is in the documents and what they reveal about the government’s activities, not the man. However, we also believe that it is time to recognize that Snowden’s actions were in the public interest — and indeed, that they will continue to benefit us, as we continue to push for vital, necessary reforms to surveillance, as well as to increase oversight and transparency. By blowing the whistle, Snowden has reinforced the central democratic value of informed debate and decision-making, on a global scale.

So, while Edward Snowden is not the story, he made the story possible. This is why the European Parliament passed a resolution calling for criminal charges against Edward Snowden to be dropped. It is also why Access Now joined the Pardon Snowden campaign. That is the right response — not forcing Snowden to defend himself against the Espionage Act in the U.S., an overbroad piece of legislation, nearly a century old, that would give him no hope of having a fair day in court. There would be no real justice for Snowden under this law.

As human rights defenders, we are proud to add our voice to the many other voices asking President Obama to pardon Snowden. Please join us.

P.S. — Real talk. Snowden made an important contribution to the conversation about human rights and surveillance, but there are many others whose actions have pushed the debate forward, and who are otherwise working to safeguard our right to privacy. On the flip side, there are those seeking to authorize the rights-harming practices Snowden revealed. Every year, Access Now recognizes human rights Heroes and Villains of Human Rights and Communications Surveillance. These awards let us honor those who follow the 13 international “Necessary and Proportionate” principles, and name and shame those who violate them. In 2014 — the first year we presented the awards — we named Edward Snowden a hero. We hope to encourage more people to stand up for these principles, which are vital to the defense of human rights in the digital age.