It was 21h32 on November 13th when time stopped in France and around the world as Paris was attacked in its heart. One hundred and thirty people were killed while enjoying dinners with friends, celebrating birthdays, and dancing at a concert. The French government, with the support of most of the population and political groups, rapidly declared a state of emergency that was initially scheduled to last 12 days. This drastic measure, not used since World War II, altered the normal balance of powers in France, giving more discretion to the President and the government.

The following week, as the police and military forces were tracking the perpetrators of the attacks, people around the world sent messages showing their support for the people of Paris, and France was moved by an unprecedented rush of solidarity. Since several suspects remained at large, the President requested that the parliament extend the state of emergency to three months, and modify the French law on the state of emergency, which dates from 1955. Parliament granted both requests with limited opposition, despite the absence of justification for the changes, and despite the fact that the modifications created new measures extending surveillance powers and limiting freedoms. More radical changes could come as the French have government has chosen this difficult period to consider modifying the Constitution, which would officially shift France from the Fifth to the Sixth Republic.

Before the attacks

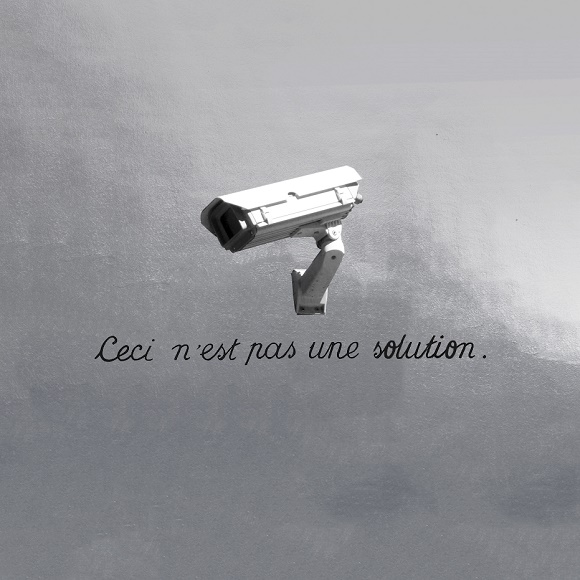

France has historically been a country with a strong tradition of defending human rights. The French Revolution and the Enlightenment inspired many human rights declarations around the world. Despite this proud record, more recently abuses and violations of those universal rights have taking place in France, as highlighted in a recent Human Rights Watch report. The past two years have been particularly liberticide. Ostensibly in response to terrorist threats, France has passed no fewer than four separate laws extending its surveillance powers since December 2014: the Military Programming law, the Anti-Terrorism law, the Intelligence law, and the International Surveillance law. Together, these laws have made France an all-seeing state, capable of monitoring the population, collecting and retaining personal data for excessive periods, snooping on the private communications of individuals in France or abroad, and the list goes on. Given France’s ever-expanding surveillance authorities, many see the government’s immediate response to the attacks in Paris as relatively measured and calm. However, it may simply be that there are not many more surveillance powers for the government to seek. That said, the newly adopted proposals have nevertheless further extended the French surveillance state to extremes never previously seen in the digital age.

What is in the new law on the state of emergency?

The law adopted on November 20th declares a state of emergency in all French territories for three months, during which:

- Warrantless house searches are authorised night and day, unless the house is occupied by a lawyer or a member of Parliament. This authority is granted by the Home Affairs minister or the Prefect of a region. The law also provides that a prosecutor be notified without undue delay. While remaining broad, this measure is a limitation of the 1955 law that authorised such house searches without notifying a prosecutor. If there is a wrongful or unsupported search, an individual can seek redress from of an administrative court.

- Warrantless searches of electronic devices are authorised. Data can be accessed and copied by law enforcement.

- The Home Affairs minister has the power to place individuals under house arrest if “there are serious reasons to believe that his/her behavior constitutes a threat to security and public order”, a provision created under the 1955 law. Now, these individuals can also be placed under invasive surveillance. While the parliament debated whether to prevent these individuals from accessing the internet, members of parliament abandoned the idea because the French constitutional court previously established that access to the internet is a fundamental right. However, the Home Affairs minister can order a limit or temporary suspension of their communications.

- The government has the right to dissolve groups or associations that “take part in the execution of acts that represent a serious infringement to public order or whose activities facilitate or incite the execution of such acts.” Under French law, public order is a subjective notion, which can be interpreted in different ways depending on the situation. It has never been defined by the French constitutional court.

- The law includes a measure to allow authorities to block websites that promote or incite terrorism, without the intervention of a judge. However, this mirrors a proposal that was already adopted in November of last year during reform of the Anti-Terrorism law, and that measure remains in effect. This makes the new measure nearly duplicative. Under the new provision, the limited oversight mechanism provided in the Anti-Terrorism law, which has been executed by the national data protection authority called CNIL, is no longer compulsory, and it is not clear whether there will be any mechanism for redress.

- Silver lining: The 1955 law gave authorities control of the media, and this is no longer authorised.

But the biggest change might be yet to come. François Hollande, the French President, has announced a proposal to modify the French constitution to “adapt the State’s response to emergency situations.” The Prime Minister has been tasked with preparing this proposal, and it is expected to be released in the next few weeks. While everyone awaits the release, several political groups are already expressing doubt as to whether the government needs to modify the Constitution of the Fifth Republic, which has been in place since 1958. A change in the constitution would officially create the Sixth Republic in France.

How is the rest of the world reacting?

Governments and lawmakers from all around the world are also responding to the Paris attacks. In the US, an already heated debate on encryption was re-invigorated after some commentators made unfounded claims that the attackers used encrypted devices or applications to communicate. In many of the discussions, participants fail to recognize that encryption makes us more secure, not less.

At the EU level, EU Justice ministers gathered November 20 for an extraordinary meeting to deliberate on next steps. The ministers discussed rules on firearms, control of external borders, information sharing, terrorist financing, and the criminal justice response to terrorism and violent extremism, the same issues they had already discussed after attacks in January. Policymakers issued a new call for the swift adoption of the EU Passenger Name Record (PNR) directive —privacy invasive legislation — despite the fact that authorities knew about all the flights taken by the Paris attackers, and the perpetrators traveled mainly in cars. There is no evidence that PNR would have helped and yet it threatens fundamental privacy even more.

On the day following the Charlie Hebdo attack, the French President said “freedom will always be stronger than cruelty.” This message should guide how our governments act during this period of crisis. We need leadership not just to keep us safe, but to protect our rights, freedoms, and democratic values.